Lately I dedided to do a bit of research on the Mounds, the family of my 3x great-grandmother Ellen. But before delving into the past and (hopefully) unearth some skeletons, let’s learn a bit more about Ellen herself.

To start with, Ellen Mound is a bit of a mystery, despite the fact that her life is fairly well documented thanks to census returns and her children’s baptismal records. I even have a photograph of her (albeit not a very clear one, and sadly her face cannot be easily made out), showing her sitting in front of her cottage in rural Herefordshire, next to her husband and youngest son, Richard Thomas.

A distant relative once shared an old family memoir about Ellen’s feisty character, so I have always imagined her to be a somewhat matriarchal and dominating sort of woman, more formidable than admirable, though this of course may be my own bias taking over. For all I know, she may have been the sweetest Granny imaginable. Ellen and I finally “met” a few years ago when I went on a trip through Herefordshire and found her grave; the sober headstone reads “Her End Was Peace“. A fine epitaph for her feisty, formidable woman. But what were Ellen’s origins? What was her background like? Why did her character turn out the way it apparently did?

Ellen was born in or around 1824 in Wormsley, a small parish a few miles outside of the city of Hereford. My research has led me to conclude that she had, at least, an elder sister called Mary, and two younger siblings called Sarah and Richard. It is quite possible that Ellen named her youngest son Richard Thomas in her brother’s honour.

The 1851 census entry confirming Ellen (under her married name) as being from Wormsley, Herefordshire.

Ellen seems to have belonged to a close-knot family. Years after her death, her sister Sarah’s granddaughter Ivy, who had recently lost her father, was taken to live with Ellen’s own son, Samuel Morris, and his family in Ivington. The Morrises raised Ivy as one of their own, but it was not until a few years ago that I actually discovered Ivy and the Morrises were related through the Mound family.

Another connection that drew the Mounds closer together was the marriage of Ellen’s brother, the aforementioned Richard, to Emma Savigar (or Saviger), who happened to be his first cousin via his aunt Mary Savigar (née Mound). This confusing web of relations made me take a keener interest in the family’s roots and background, and so this is what my research has yielded so far.

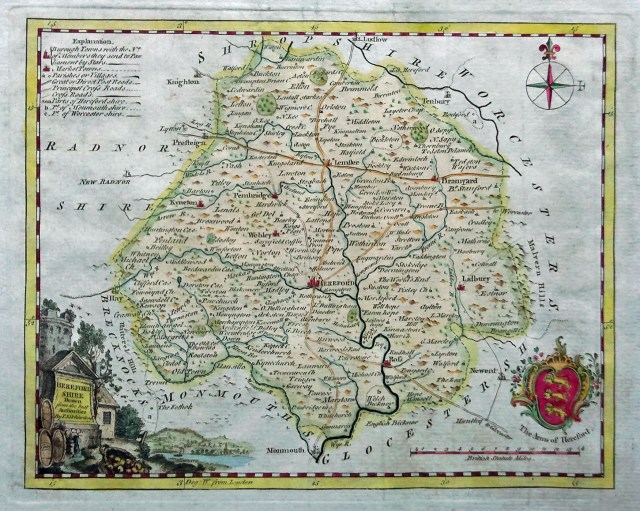

The Mounds originally came from the southern part of neighbouring Shropshire, not far from that county’s border with Herefordshire. The most distant ancestor I have managed to trace is a man called Thomas Mound, Ellen’s paternal grandfather, whose origins are, so far, a mystery. All I know is that he is likely to have been he seems to have been the church warden in St John the Baptist’s church, in the village of Hope Bagot.

Thomas and his wife Ann (whose maiden name and origins, incidentally, are just as obscure), had at least five children, all of whom were baptised in Hope Bagot: William (1796), Thomas Jr (1798), Richard (1802), John (1805) and Mary (1808). Although all five were born in the same village where their father worked, later census returns of the 19th century prove that none of them remained in Hope Bagot for very long. In fact, by 1841 they were all living in other areas of the county and of the country, leading fully independent lives from their parents and each other.

The church of St John the Baptist, Hope Bagot in Shropshire where the Mounds lived in the early 1800’s.

William Mound, the eldest of the five siblings, was christened on 1st May 1796. By the time he turned 30 he had already married a woman called Mary (maiden name unknown), who would be his companion for the next five decades of his life. The couple settled in Trysull, at the time a rural village which is now a suburb of the larger city of Wolverhampton. It was there that their first four children were born: Harriet (born in 1825), Helen (1827), Anne (1833) and Thomas (1836), the couple’s only son. The daughters’ lives remain a mystery, although the fact that little Helen doesn’t appear in any census returns makes me suspect that unfortunately she died young. A further daughter, Mary, was born in nearby Seisdon in 1838.

In 1851, 25 year-old daughter Harriet is listed living at home in Seisdon, close to Trysull, with her mother, her brother and her youngest sister Mary. Both Harriet and mother Mary worked as seamstresses, while father William worked as a groom (and consequently lived in a separate house nearby, probably in the service of a local employer). Years later, youngest daughter Mary was recorded as a dressmaker, having outlived her parents.

The family’s only son, Thomas, began working at a very early age. By 1851 he was in service, probably working as a stable-boy, since he would later go on to become a groom and then a coachman, thus following in his father’s footsteps. He married Mary Ann Lewis and moved to Merseyside, where their brood of (at least) twelve children were born over the next 24 years of marriage. I am far from having traced their individual personal stories so far, so for the time being I will just mention them by name: Belinda Boyd (later Haslam), Harriet (later White), William Lewis , Thomas , Ellen Gertrude (later Corrin), Mary Louise , James , Annie , Henry , Charles , Emily Louisa and Arthur Edward. Phew! I wonder if any of their many descendants are reading this article right now?

The father of this proud brood lived until the year 1914, dying a few months before the outbreak of World War I.

Stay tuned for more updates on the Mounds, as next time I will be tackling the other children of Thomas the church warden.