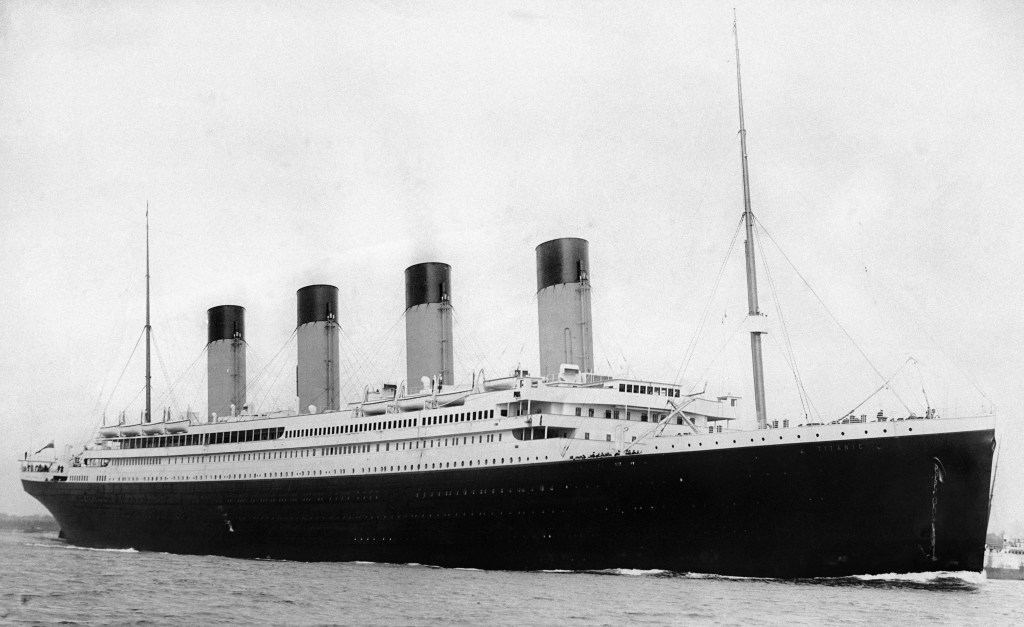

Anyone who knows me will be well aware that one of my biggest passions – some would call it an obsession – is the story of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, arguably the most famous maritime disaster in world history. The story of the (then) largest ship in the world, believed by many to have been unsinkable, crossing the North Atlantic on her maiden voyage to New York, striking an iceberg and sinking in just two hours with a loss of over 1,500 souls, has quite simply fascinated me since I was a child.

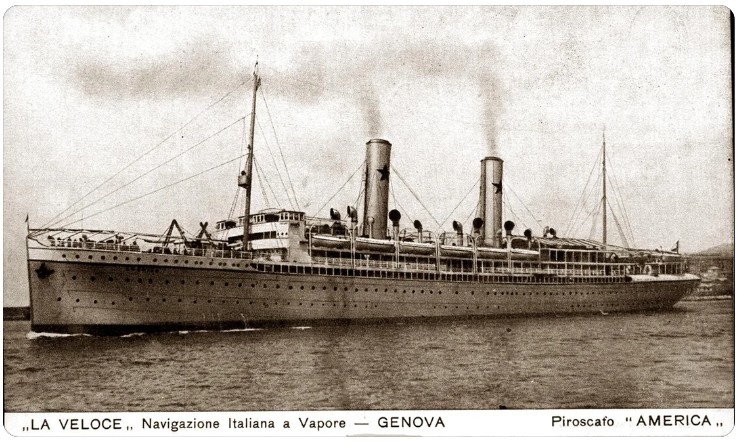

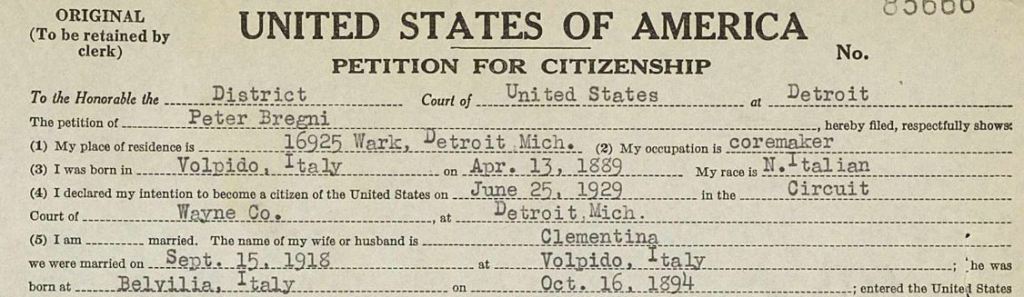

I often think about how my own relatives may have reacted to the sinking, and how it may have affected them when they themselves travelled across the Atlantic. After all, my great-grandparents came and went from Spain to Cuba several times at the turn of the century; my Italian great-grandfather emigrated to the US only two years before the Titanic‘s doomed voyage; and his future wife, my Italian great-grandmother Giovanna, actually sailed from Genoa to New York when she was only 17 years old, a mere seven months after the sinking. I’m sure the event must have prayed on her mind constantly during her fortnight-long crossing!

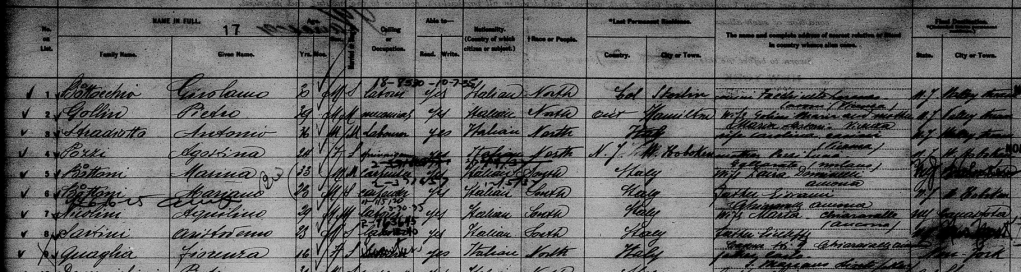

Because the Titanic had set sail from England (specifically, from the port of Southampton), before picking up some continental passengers at the French port of Cherbourg, and then called at Queenstown (today called Cobh) in Ireland, the ship carried comparatively few passengers and crew from southern Europe. Most Italians of the age, like my own great-grandparents, usually sailed either from Genoa, Naples or Marseille. There were of course exceptions, and that does not mean that there were no Italians aboard the Titanic itself, but most of them were neither passengers nor members of the crew: they were employees of two exclusive restaurants, as related below.

The Encyclopedia Titanica lists a full 45 Italian nationals aboard the ship during the fateful voyage. Perhaps the best-known was Victor Giglio, who had been born in 1888 Liverpool to an Italian father and an Egyptian mother; Giglio worked as a manservant to American businessman Benjamin Guggenheim, who was returning to America accompanied by his French mistress, Leontine Aubart. Giglio, Guggenheim and the latter’s chauffeur died in the disaster, but Aubart and her maid survived.

Also aboard the ship were newlyweds Mr and Mrs Sebastiano Del Carlo, who boarded the Titanic at Cherbourg as second class passengers en route to California. Mrs Del Carlo survived the sinking, but her husband did not. His body was eventually recovered, and today lays buried in Altopascio, in the Italian province of Lucca.

One of the best-known Italians on the Titanic was undoubtedly Gaspare Antonio Pietro (though known as Luigi) Gatti, a very successful restaurateur who, after earning a name for himself in London, had been engaged by the White Star Line to manage the ship’s à la carte restaurant and fashionable Café Parisien, which was particularly popular among young first class passengers. Gatti employed a number of Italian and French members of staff, including several relatives… as well as a man to whom I may well have a distant family relationship!

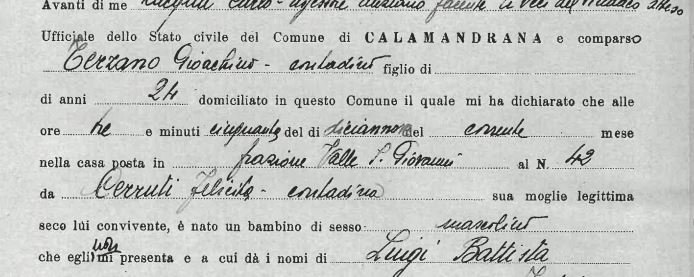

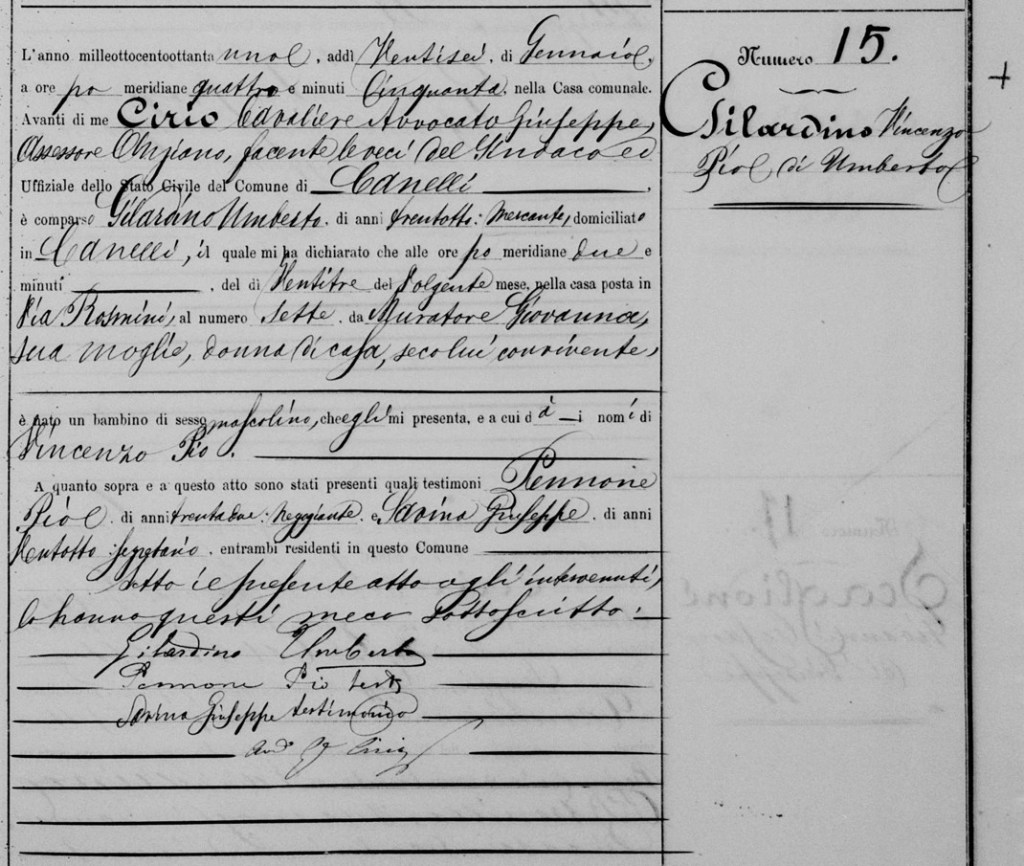

Vincenzo Pio Gilardino was born on 23 January 1881 in the Italian town of Canelli, in the northwestern region of Piedmont. His father, Umberto, was a merchant from Canelli, while his mother, Giovanna Muratore, came from the nearby village of Fontanile, where her father Stefano worked as a baker. The couple raised their large brood of at least eleven children. Vincenzo was their third youngest child, and was reported to be extremely close to his elder brother Gustavo, who had been born in 1879.

The Gilardino family first lived on Via Degli Ebrei before relocating to Via Rosmini, where Vincenzo was born. Vincenzo’s father Umberto belonged to a large family; his elder brother, Giuseppe Gilardino, fathered at least nine children with his wife Vincenza Terzano, whose lineage I explore further below.

Vincenzo’s paternal grandparents were called Pietro Gilardino and Anna Discalzi; she died before 1868, the year of Vincenzo’s parents’ marriage. His maternal grandparents, on the other hand, were Stefano Muratore and Regina Gilardino (the common surname of Gilardino on Vincenzo’s paternal and maternal family could suggest a possible kinship between Vincenzo’s parents).

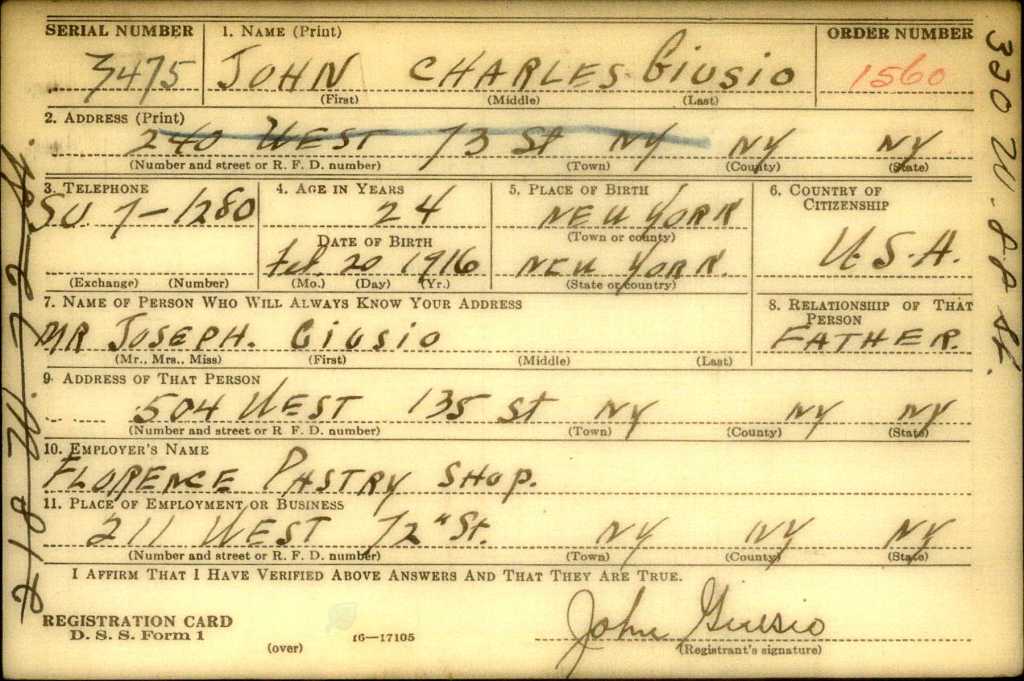

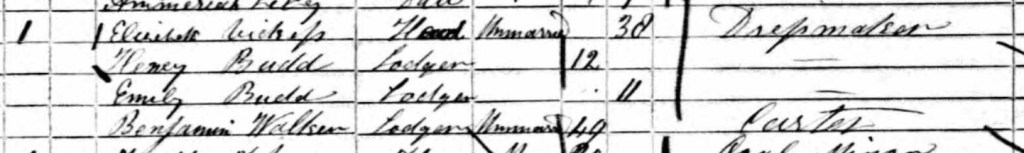

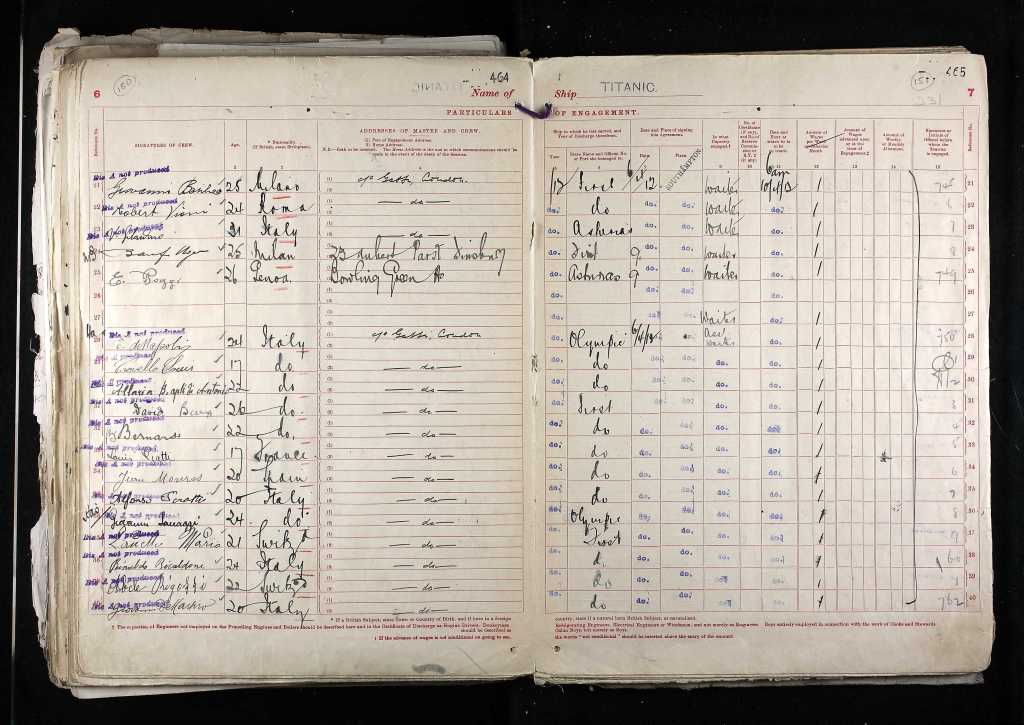

Sometime in the 1890s, when he was still a young man, Vincenzo moved to England in search of employment. According to Encyclopedia Titanica, his niece later claimed that his family were anxious for him to return to Italy, and sent his brother Gustavo to persuade him, but Gustavo not only failed in his mission – he actually ended up staying in England himself, settling in Manchester. Meanwhile, Vincenzo worked as a waiter on several transatlantic ships, often covering the route to Buenos Aires. At some point in his careeer, he came to be in the employment of prestigious restaurateur Luigi Gatti. So, when signore Gatti announced that he had secured a concession to run two of the Titanic‘s restaurants, Vincenzo would have leapt immediately at the opportunity.

Vincenzo remained geographically and emotionally close to his elder brother Gustavo, who by 1911 was a confectioner running his own business just outside Preston, where he lived with his English-born wife Agnes and their daughter Catherine (known as Rina). It was to Gustavo that Vincenzo would send his last letter on 6 April 1912, four days before leaving Southampton:

Dear Gustavo,

I hope that you have received my postcard from Belfast. I am sorry I couldn’t have written to you sooner. I was waiting for a letter from you to give you a piece of good news. On the 10th I’ll leave on the Titanic, the biggest ship in the world. I’ll have to shave my moustache, but never mind! As soon as I return, I’ll be able to tell you if the position is good or not, but I am hopeful. As soon as you receive this, write to me quickly, so that I may have news from you before departing.

Many greetings and kisses to you, Agnese and Rina.

Your brother Vincenzo

Little is known of Vincenzo’s movements during the subsequent four-day voyage, though he must have been kept very busy by his work in completely new surroundings. Most of his fellow colleagues were Italian, which would have given his working environment an air of familiarity. However, when the ship struck the iceberg before midnight on 14 April 1912, Vincenzo, like most of the men onboard, had little chance of escape. The Titanic was equipped with only twenty lifeboats, which were enough to accommodate a third of the all the people aboard. As it turned out, only 700 of the 2,200 people on the ship survived.

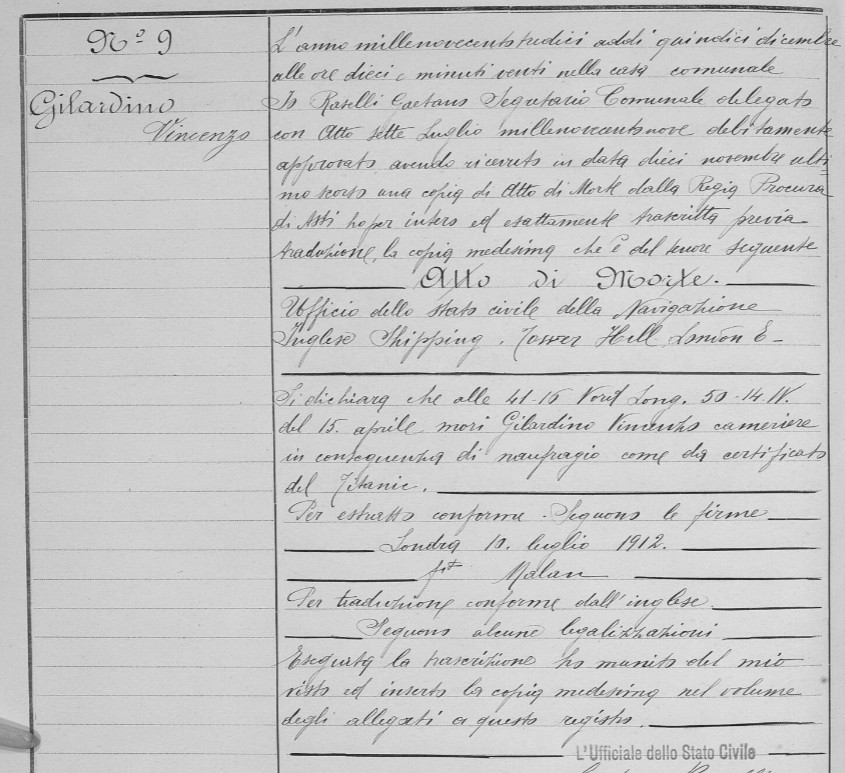

Rumours abound about how foreigners and third class passengers were deliberately or accidentally kept below deck during the Titanic‘s sinking. While such accounts are unreliable, and probably derive from a combination of factors (including lack of communication, the ship’s complicated layout, lack of lifeboat drills during the voyage, and language barriers between passengers and crew), one persistent rumour is that Italian staff were locked up during the sinking for fear that they would become hysterical and cause panic among the gentlefolk of first class. Whether this is true or not, and whether Vincenzo was among those supposedly kept under lock and key, is not known. What is certain is that all of signore Gatti’s staff (except two female cashiers and a kitchen clerk) perished in the disaster, including Vincenzo Gilardino and Luigi Gatti himself.

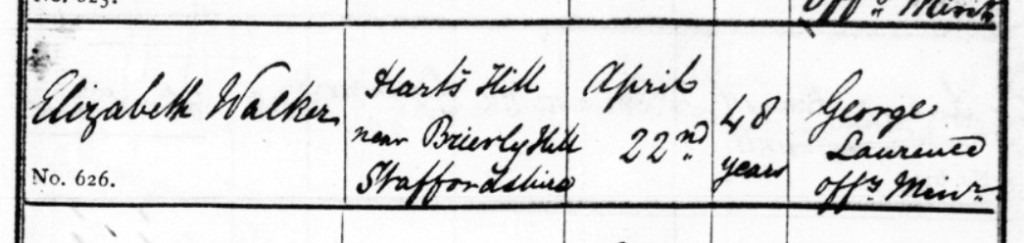

Vincenzo’s body was never recovered, and if it was, he was never identified. However, years after his death, his 18-carat gold pocket watch was retrieved from the ocean floor, and is today part of the Titanic Honour and Glory exhibition that tours the world.

While Vincenzo’s story is certainly tragic, like that of the other 1,500 victims of the Titanic disaster, I am somewhat intrigued by the fact that his mother came from the village of Fontanile, where my own great-great-grandmother Francesca Frola was from. It will take some research to prove whether Vincenzo and Francesca had any ancestry in common, but the possibility that they were related is not all that improbable, considering the village’s small population.

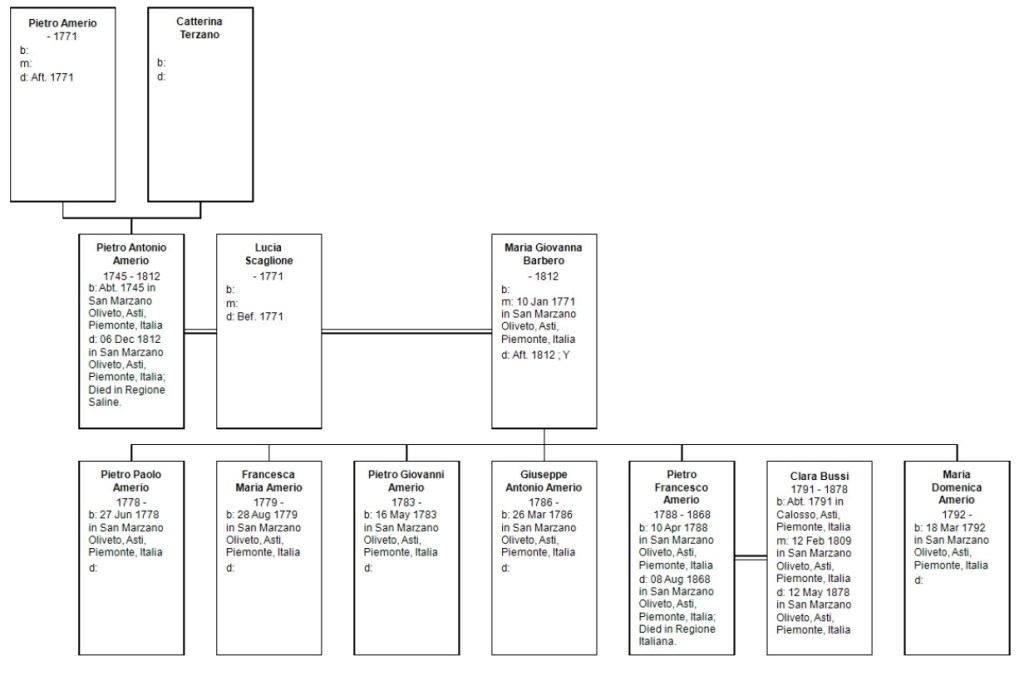

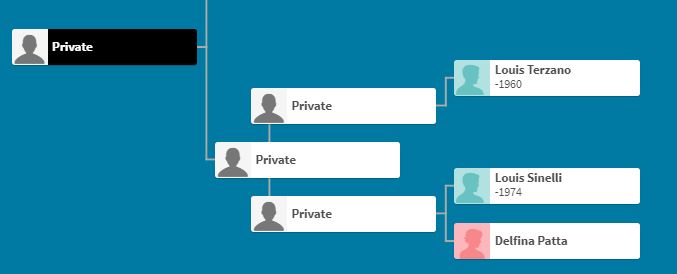

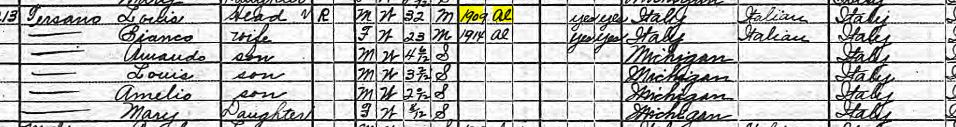

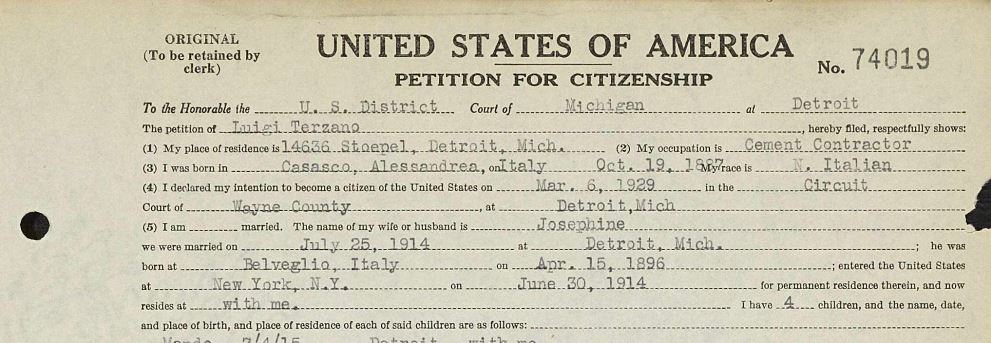

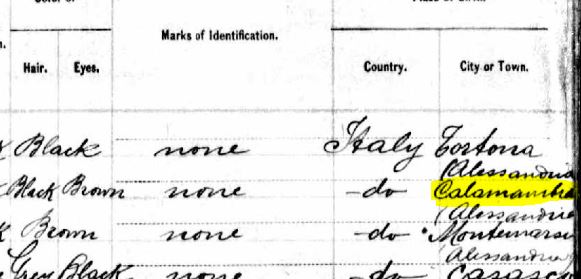

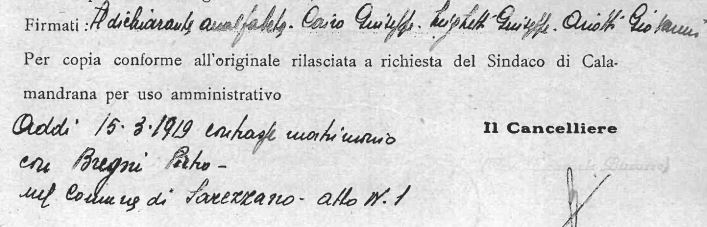

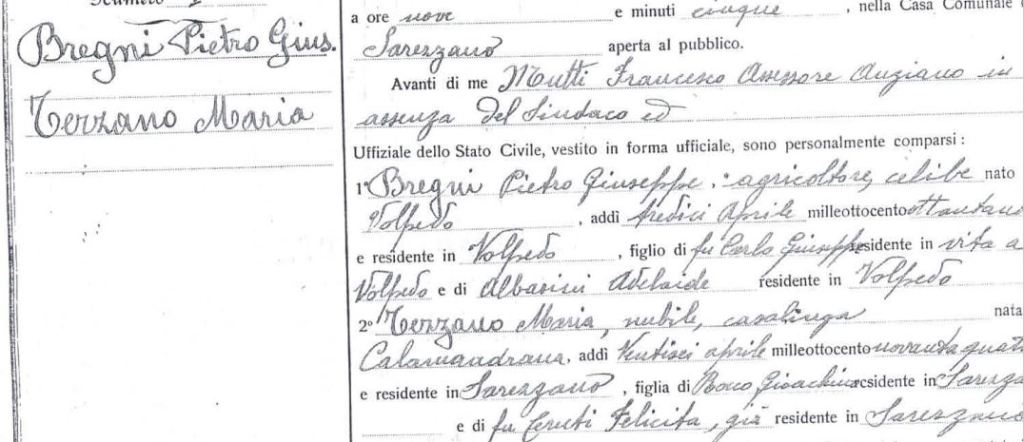

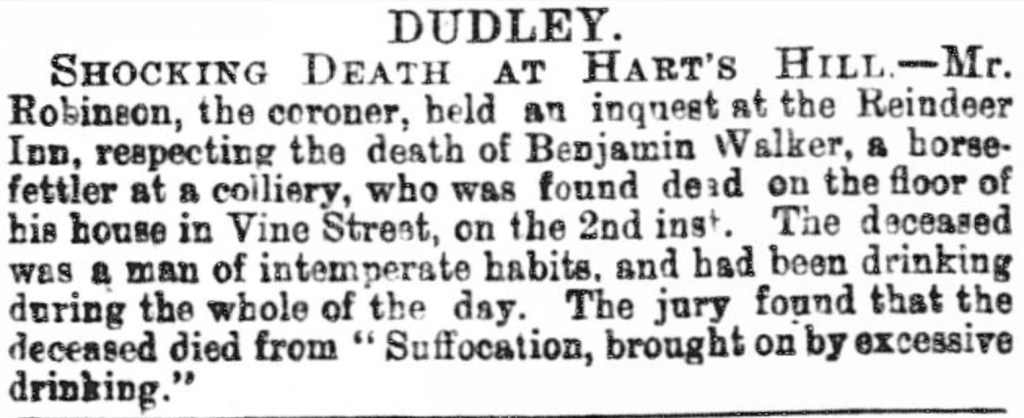

There is another curious family link to Vincenzo I would like to tell you about. Remember how I told you that his father Umberto, who was born in about 1843 in Canelli, was the son of Pietro Gilardino and Anna Discalzi? Well, the couple had at least another son called Giuseppe, who was three or four years older than Umberto. He eventually would go on to marry a woman called Vincenza Terzano, who was born in 1838, also in Canelli, to a well-to-do pharmacist called Stefano Giuseppe Terzano and his wife Maddalena Rossero, who came from Susa. Stefano Giuseppe Terzano became a pharmacist like his father, Bartolomeo Terzano, who was born in 1786 in San Marzano Oliveto – my great-grandmother’s birthplace! I have managed to follow his paternal lineage back to his father Stefano Terzano, who married a woman called Maria Giuseppa in the 1770s. As I have the surname Terzano several times in my family tree, and that Vincenza’s ancestors came from the same village as hers, I am fairly confident that I am indirectly related (through his aunt-by-marriage) to Titanic victim Vincenzo Gilardino. Further research will definitely be required to prove the connection.

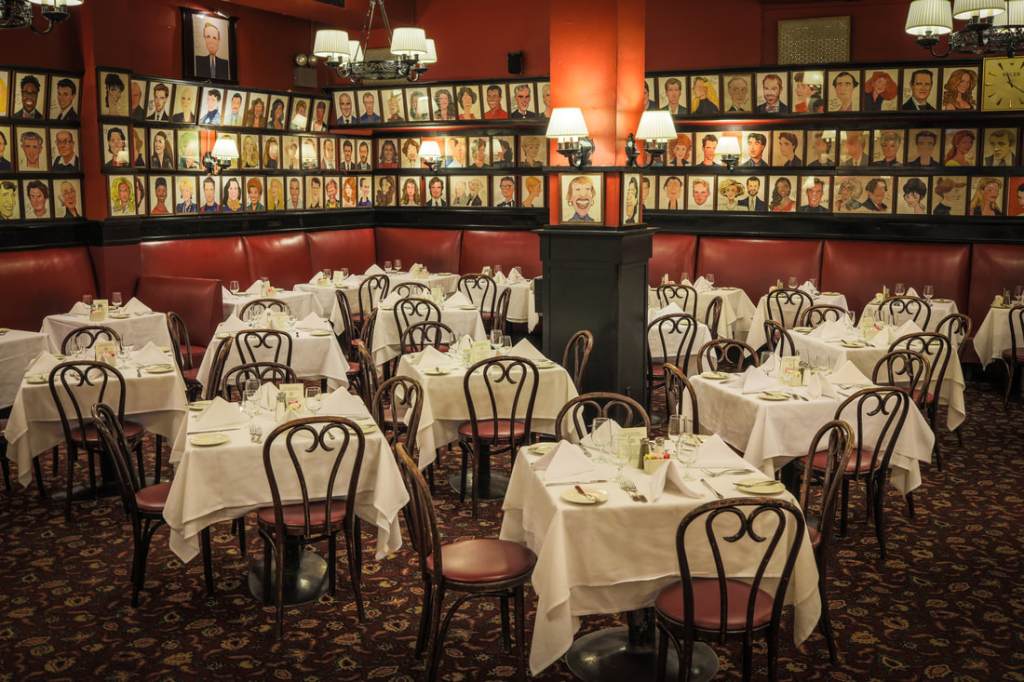

What is certain is that through his uncle Giuseppe and aunt Vincenza, Titanic victim Vincenzo Gilardino had a very interesting connection to the catering world: he was related to the founder of the well-known Broadway restaurant Sardi’s.

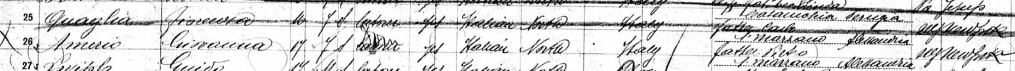

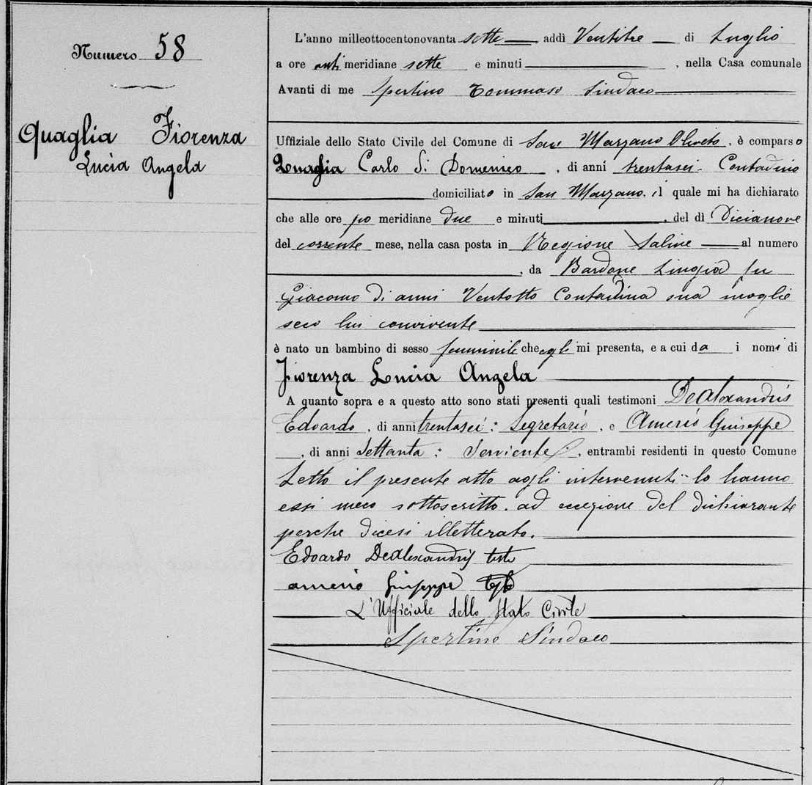

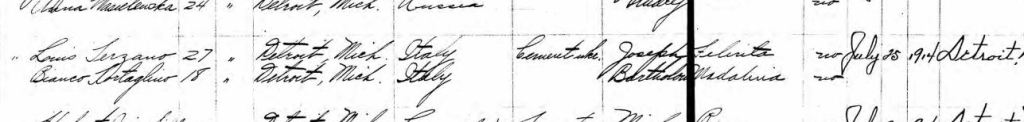

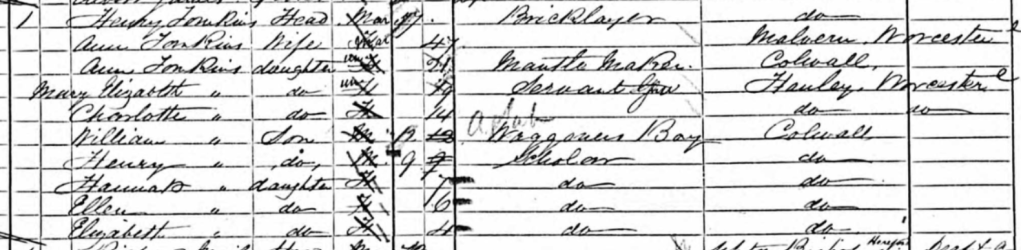

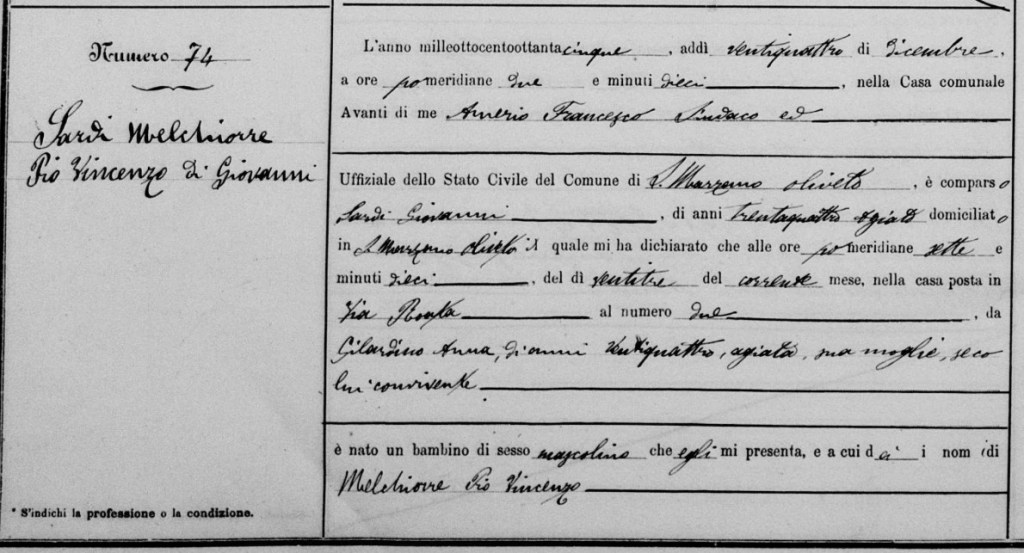

Vincenzo’s paternal uncle, Giuseppe Gilardino, and his wife Vincenza Terzano/Terzani, had at least nine children, all born in Canelli in the 1860s and 1870s. Among the eldest was Anna Maddalena Gilardino, who in 1880 married a local landowner with the somewhat pompous name Giovanni Battista Cipriano Paolo Baldassare Emilio Sardi. The couple settled in nearby San Marzano Oliveto (the vilage where my own great-grandmother was from) and had eight children between 1880 and 1891.

The couple’s fifth son, Melchiore Pio Vincenzo Sardi, was born in 1885, and like his unfortunate cousin, he also lived in England until his early twenties, when he emigrated to America. There he would be known as Vincent Sardi.

In New York he married his Italian-born wife Eugenia, known as Jenny, and the couple subsequently opened their first eatery in 1921, although they were forced to close down a few years later when the building was due for demolition. Vincent and Jenny Sardi then decided to open a second restaurant at 234 West 44th Street, between Broadway and Eighth Avenue, in Manhattan’s Theater District.

The restaurant, called Sardi’s, quickly became not just an institution in Broadway theatre, but a symbol of New York pop culture. Over the years, Sardi’s was a pre- and post-theatre hangout, as well as a location for opening night parties. The idea of the Tony Award was devised in this very restaurant.

So there you have it – not only might I have family ties to a Titanic victim, but I might also have a link to one of the best-known restaurants in New York City! I guess I know where I’ll be having dinner next time I’m in Manhattan!