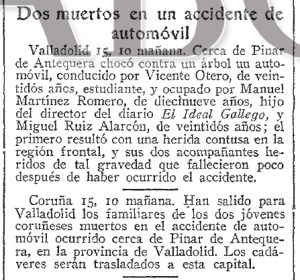

Like so many other great British female authors, such as Virginia Woolf or the three Brontë sisters, English novelist Jane Austen (1775-1817) was a wonderful and prolific writer, but left no children. But although there are no descendants of the creator of great works like Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility or Persuasion, Jane Austen’s large family is an interesting genealogical case in itself.

Jane Austen was born in 1775 in Steventon, Hampshire, the second daughter and seventh child of an Anglican clergyman, the Reverend George Austen, who had himself been born “on the lower fringes of the English landed gentry”. Reverend Austen was descended from a family of woollen manufacturers from Kent and Sussex who had gone up in the social scale several generations earlier. His wife, Cassandra (formerly Leigh), could boast greater connections with the English aristocracy. Cassandra’s paternal grandmother, Mary Brydges (1666-1703) was the eldest child of James Brydges, Baron Chandos of Sudeley, who in 1680 was appointed Royal Ambassador to the Sultan’s Court in Constantinople. By going up a few generations back, we discover that Jane Austen’s family tree is populated by Greys, Staffords, Nevilles, Throckmortons, Fitzalans, Beauchamps, Beauforts and, ultimately, to the most illustrious of all ancestors, King Edward III.

Like her elder sister Cassandra, Jane Austen left no descendants, but their large army of brothers did have in most cases a significant amount of progeny. Here is a relation of their names, their spouses, and a brief account of some of their descendants’s lives:

1. James Austen (1765-1819) became a clergyman, like his father. He was married twice, his first wife being Anne Matthew, who died in 1795 after giving him a daughter called Anna (this girl would go on to marry Benjamin Lefroy, the nephew of the more famous Tom Lefroy, who had earlier courted her aunt Jane and was, quite possibly, the author’s love of her life). James Austen married as his second wife Mary Lloyd, was was not only a great friend of Jane’s, but whose cousin and brother-in-law Thomas Fowle had once been engaged to the other Austen daughter, Cassandra. This second marriage produced a son, Edward Austen-Leigh (1798-1874), and a daughter, Caroline, who died unmarried in 1880. Nephew Edward, who would go on to become his famous aunt’s first biographer, married Emma Smith in 1801 and sired ten children. One of them, Chomeley, married the daughter of the Protestant Archbishop of Dublin, while other male descendants also joined the clergy. Another descendant, Lionel Austen-Leigh, who was “a land surveyor who went to Victoria British Columbia when it was an ‘outpost of Empire'”, emigrated to the United States in 1937.

2. George Austen (1766-1838) was the only one of Jane’s brothers who never married. He was reportedly born an invalid, a general term to describe someone who was either physically or mentally handicapped. Aged four, he was unable to speak properly, and during one of his aunt’s visits to the Austen home, it became clear that the child was “backward”. Suffering from terrible epileptic seizures, the boy never learned to talk, and was finally entrusted to a foster family who took care of him. It was not until he was in his early teens that it was judged safe for his sister Jane to pay him a visit. He died, in obscurity, in the late 1830’s, forgotten by all.

Edward Austen (later Knight), Jane’s elder brother, is the ancestor of actress Anna Chancellor, adventurer Denys Finch-Hatton and British peer and film producer John Brabourne.

3. Edward Austen, later Knight (1768-1852), was introduced at the age of 12 to Thomas and Fanny Knight, wealthy childless cousins on his father’s side. The Knights decided to adopt Edward, who from 1812 onward used the surname “Knight” instead of Austen. He married Elizabeth Bridges in 1791, and the couple had eleven children, including one of Jane Austen’s favourite nieces, Fanny Knight (1793-1882). Edward inherited from the Knights a total of three estates, the libraries of which were extensively used by his novelist sister. He also inherited the rectory at Steventon, where the Austen children grew up, but in the 1820’s he had it knocked down after the building was damaged in a flood. This explains why Jane Austen’s birthplace no longer exists. Fanny Knight married Edward Knatchbull, Baronet, whose son Edward became Lord Brabourne. His descendant John Ulick Knatchbull, 7th Baron Brabourne, married the daughter of Lord Mountbatten, who was killed by the IRA in 1979 along with one of his grandsons and the elderly Lady Brabourne, his daughter’s mother-in-law. Edward Knight’s granddaughter Fanny Rice (1820-1900) married the Earl of Winchilsea and Nottingham; her grandson Denys Finch-Hatton settled in British East Africa, and his romance with the novelist Karen, Baroness Blixen was immortalised in her autobiography Out of Africa, which was later turned into a movie. Another of Fanny’s grandchildren was Muriel Finch-Hatton, whose daughter Sylvia Paget, OBE, was the grandmother of actress Anna Chancellor, who played the haughty Miss Caroline Bingley inn the famous BBC adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

4. Henry Thomas Austen (1771-1850) was Jane’s favourite brother. He was known to be witty and enthusiastic, but unfortunately not always successful in his business interests. His wife was his first cousin Eliza (née Hancock), the daughter of Jane Austen’s paternal aunt, Philadelphia Austen. Eliza, who was born in Calcutta in 1761 the possible daughter of her godfather Warren Hastings, had been previously married to a French aristocrat, Jean Capot, Comte de Feuillide, who was executed at the guillotine in 1794; she had one son by her first marriage, but the boy died in his teens in 1801. Eliza herself died in 1813, without leaving any descendants by her second husband Henry Austen. Two years later Henry became bankrupt, and later would go on to become a Calvinist-leaning minister. It was he who would see his sister’s two novels, Persuasion and Northanger Abbey, through to the printing press. In his late 40’s he married his third cousin, Eleanor Jackson (a descendants of an earlier Austen ancestor), but they had no children.

5. Cassandra Austen (1773-1845), Jane’s only sister, was her closest friend and confidante throughout her life. Although she burned many letters written by Jane after the latter’s death in 1817, there are 100 or so letters sent by the sisters to each other which give an interesting and intimate insight into their unique relationship. Cassandra became engaged, when she was quite young, to Thomas Fowle, a cousin of her brother’s wife Mary Lloyd, but it was to be a long engagement without a happy ending. Thomas died of yellow fever whilst in the Caribbean in 1797, and Cassandra vowed never to marry anyone else. The experience may have inspired Jane to write critically of “long engagements”, which she deemed “uncertain” in her last completed novel Persuasion. Cassandra lived very much like her sister, at the mercy of wealthier relatives, and often portrayed her siblings in sketch books. She survived Jane by almost three decades, and died in 1845 in Chawton, Hampshire.

6. Francis Austen (1774-1865), known as Frank, joined the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth along his younger brother Charles. He fought in the British Navy during the Napoleonic wars, and like his brother he rose to the rank of admiral. The more famous Admiral Horatio Nelson once remarked that Frank Austen was “an excellent young man”. In 1795 he was part of the naval squadron that escorted Princess Caroline of Brunswick to England, where she was to infamously marry her cousin, the future George IV. After the defeat of Napoleon, Frank was transferred to the North America and West Indies Station in 1844 and was promoted an Admiral of the Red in 1855. It is said that Frank Austen’s rapid early promotions were largely due to the patronage of the powerful Warren Hastings, who was a friend of the Austen family and was alleged to be the natural father of Frank’s cousin (and later sister-in-law), Eliza de Feuillide. In 1806 he married Mary Gibson, who gave him eleven children. After her death in 1823 he married secondly Martha Lloyd, his sister-in-law’s younger sister. This second union left no children, but there are many descendants alive today descended from his first marriage.

7. Charles Austen (1779-1852) was also, like his brother, a navyman. He served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars, eventually rising to the rank of rear-admiral. In 1807 Charles married Frances Palmer, the youngest daughter of the late Attorney-General of Bermuda. The couple had four daughters, of whom two died young; the other two died as adults, and unmarried. After the death of Frances in 1814, Charles married his late wife’s sister Harriet in 1820. The couple produced four children, two of them sons, and one of whom, Charles John Austen, followed his father into the navy and died in Guadeloupe in 1867, leaving numerous descendants.

Here is an interesting documentary about Jane Austen’s life, which given an insight into her family and her personal life:

For specific details about Jane Austen’s family, I recommend the following website, compiled by one of her many relatives, Ronald Dunning.