The pink ribbon, the symbol of cancer awareness and battling cancer – but the illness continues to be a taboo subject for many people because of its perception as a social disease.

Author’s Note: The below was written on 27 April 2017, and updated on 30 November 2018.

We have all met someone who has had cancer. You might even be a cancer survivor yourself. Or you may well be battling cancer at this very moment, as you read these lines.

The sad truth is that cancer has become one of the most common illnesses among human beings, and one of the world’s biggest killers today. Happily, significant advances in medicine and science are enabling medical teams around the globe to treat and in many cases cure cancers which one or two decades ago ago would have been incurable from the outset.

Cancer is very often wrongly perceived as a “recent” illness. This is because of its commonality and the frequency with which it strikes nowadays, and because in our modern lives it has replaced smallpox, cholera, typhoid and tuberculosis as one of the biggest threats to human health. And yet, for all its apparent newness, cancer and the tumours that it causes have been present for millennia. In fact, cancerous tissue has been found on Egyptian mummies which date as far back as 1600 b.C.!

The reason why I think cancer is perceived as a “recent” disease is because it used to be much less common in the past, as people then, both rich and poor, were far more likely to die of many other illnesses and at a much younger age. To put it bluntly, our ancestors usually died before they got a chance to develop a slow-acting illness like cancer; in other words, people rarely lived long enough to suffer from cancer. It is only thanks to medical advances and improvements in public hygiene and sanitation that cities and towns began to offer better living conditions, and so, with the decline of common epidemics came the rise of other illnesses not directly (or at least, not so directly) linked with living conditions.

In my personal case, cancer has been present in my family for generations. How many generations, we will probably never know, but it has certainly been there for decades, and chances are it will unfortunately appear again in the near future.

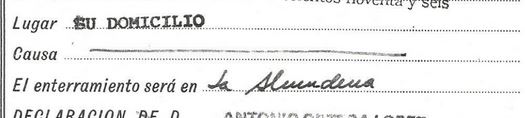

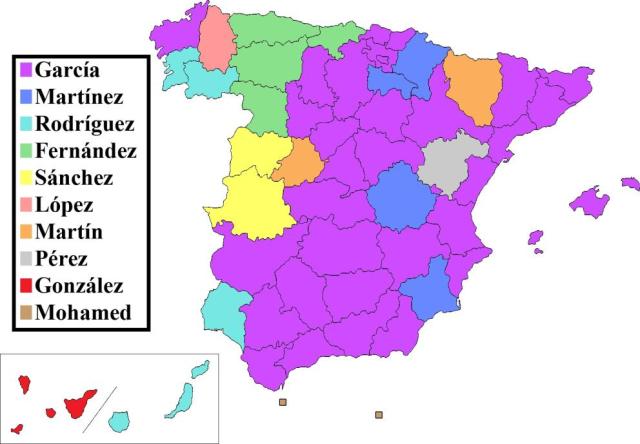

I grew up being aware that my Spanish maternal grandfather had died of oesophageal cancer in his late 50s. By the time he decided to go to Madrid to see a specialist, the cancer was already incurable. In fact, it consumed him so quickly that he made his way back home in a coffin. Sadly, his younger brother (my Mum’s uncle), died of exactly the same type of cancer two years later, in spite of the fact that he was physically active, was not a smoker and didn’t drink a drop of alcohol (unlike my grandfather, who took pleasure in his daily glass of wine and smoked cigars regularly). I was therefore very aware that the dreaded illness had struck two members of my immediate family not long before I was born, and some forty years after they had both lost their mother to… yes, you guessed it: cancer. My great-grandmother Hermelinda died at the age of 49, consumed by breast cancer.

For years all this seemed a simple, straight-forward case of family misfortune. I accepted the fact that cancer had made its entry into the family, and hen vanished equally quietly. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that I realised illnesses like cancer don’t simply “vanish”: one of my Mum’s sisters was diagnosed with cancer for a second time in her life when she was in her late forties, and succumbed in 2004.

A few years went by. I was by then living abroad, and then I got the dreaded phone call from my Mum to tell me she had noticed a lump on one of her breasts and that she had been diagnosed with cancer. Luckily, following her sister’s demise, my Mum had taken the precaution of going to the doctor for an annual check-up, and made sure she was thoroughly screened for breast cancer.

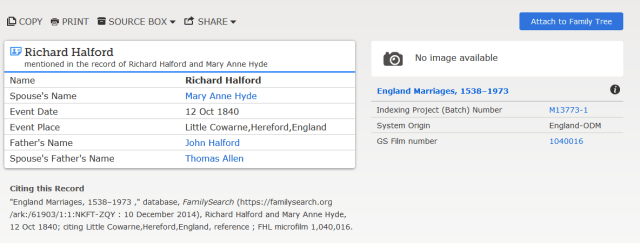

In a way, for me the diagnosis wasn’t a huge surprise, but I don’t think any of us expected what followed next: not only did my Mum have cancer in one breast – she had cancer in the other breast too, and (and this is the extraordinary bit) both cancers were not linked to each other! Her doctor told her it was a very rare case, and soon started asking questions about the recurrence of cancer in my maternal family. My Mum didn’t think twice about telling him about her recent family history (her sister, her father, her uncle, her grandmother…), but soon she seemed to be getting onto something much more sinister than pure rotten luck.

By the time of my Mum’s diagnosis, I was well into my tenth year into family research, so you will understand my “excitement” when she started asking me questions about various dearly-departed relatives, and what they had died of. Curiously, until that time I had not paid much attention to death certificates, having focused mainly on expanding my family tree’s collateral branches and ordering birth and marriage certificates, but I soon began delving into the necessary documents to start filling in the gaps.

Knowing that my great-grandmother Hermelinda had died of breast cancer in 1937, I started looking at her immediate family. She had been one of ten children (one boy and nine girls). The son died of asthma and heart failure at an advanced age, while three of the girls died very young of common infant illnesses, so I decided to focus my attention on the other sisters who did make it to adulthood. The results were shocking: of the five remaining sisters, four died of cancer: there was one case of liver cancer, two of breast cancer, and one of lung cancer.

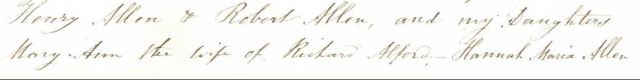

My grandfather in the 1930’s flanked by his mother (r) and her sister. All three died of cancer.

I immediately jumped back a further generation to try and find a link to any other cancer-related deaths on either side of their parents’ family. My great-grandmother’s mother, Dominga, died of a “diabetic coma” – in other words, not a cancer-related disease. My great-grandmother’s father, however, did die of cirrhosis of the liver, which apparently can be a linked to liver cancer (which as we have seen was the cause of death given for one of his ten daughters). This seemed to me like a possible lead, so I decided to research further researched how my great-great-grandfather’s ten brothers and sisters’ ended their days.

Again, I was compelled to discard two of his sisters who had died in infancy of unknown causes, as well as a third brother who had died of smallpox at the age of 13 months. Of the remaining two brothers, one died of what was diagnosed as chronic gastroenteritis, which in itself does not imply cancer, but the fact that it was recorded as “chronic” makes me wonder whether it may have been something else that brought on his demise?. The remaining brother apparently died of broncho-ataxia (a lung ailment) and pellagra (a deficiency disease). Thus, no immediate signs of cancer among the brothers… but what about the sisters?

My great-great-grandfather had a total of seven sisters; leaving out the two girls who had died in infancy, I had to find the cause of death of the remaining five. One remains elusive to this day, so I have no way of knowing yet when or how she passed away, but the other four offered further clues. The elder of the four, called Delfina, died at the age of 63 in 1918 due to a carcinomatose organic cachexia; her next sister, Carmen, had died eight years before at the age of 52 of a mamarian schirrus (or hard tumor). The next sister, Estrella, died at the age of 46 in 1912. Her youngest sister, Encarnación, had died four years previously of a reproduced mammarian carcinoma aged only 39. She left a widower and three infant children aged between five and one years of age – I later discovered that her younger daughter also succumbed to breast cancer aged 53.

I was obviously on the right track to discover from which branch my Mum had inherited the cancer gene, if indeed there was one, but my research got tougher as I moved back in time. Neither of my great-great-grandparents’ parents, Francisco and Rosa, appears to have died of a cancer-related illness, and in fact both reached a fairly advanced age. I thought then of turning to their respective siblings, but my great-great-great-grandfather Francisco only had one brother (who died, of unknown causes, at the age of 57) and the mother only had one brother who died young and one sister who, somewhat suspiciously, died of “rheumatism and flatus” (this again does not necessarily imply cancer, but who knows if rheumatic-type pain could have been caused by an internal tumour of some kind?).

Any additional research into the origins of cancer beyond this generation appears impossible, as the cause of death for my ancestors in the early 19th century was not recorded. One possible lead which I may never be able to provide comes via Rosa’s family. Her mother, Carmen, died at the age of 35 of “a natural death” – possibly a euphemism for cancer? Alas, I don’t think I will ever find out.

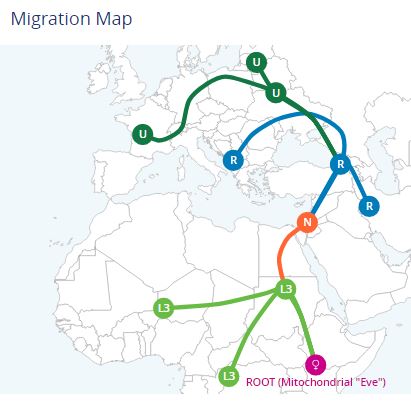

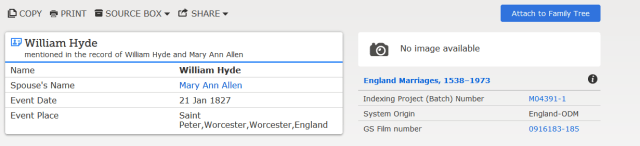

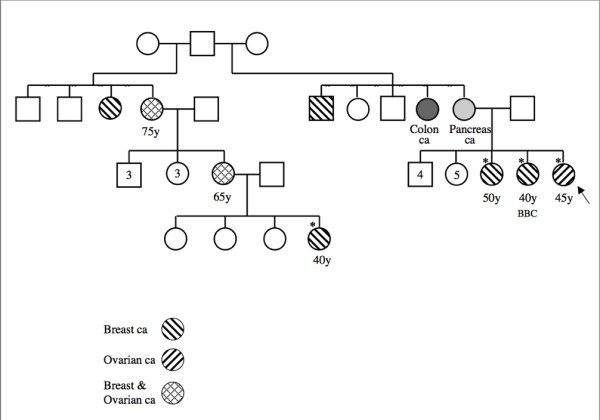

With such a medical history, my Mum’s oncologist took immediate action and sent her Mum to do some tests for BRCA1 and BRCA2, hereditary genes which are linked to specific types of cancer (breast, pancreatic, prostate and melanoma), most of which can be found in my recent family history. Unsurprisingly, my Mum tested positive for one of those mutations (BRCA2), as did one of her younger sisters and the latter’s daughter. Other members of the family have decided not to test or are currently waiting for their results. In the meantime, my Mum’s eldest sister lost her battle against pancreatic cancer. She had decided not to do the BRCA2 genetic test.

A family tree showing members of a family and the inheritance pattern of breast and ovarian cancer.

Unlike my aunt, and perhaps prompted by my natural curiosity as a genealogist to unravel family mysteries, I decided to test in order to find out if I too was a carrier of the BRCA2 gene, and thus if my chances of developing cancer were significantly higher than average. My brother also decided to test. Much to our relief, our results came out negative. Now, this does not mean that we will never have cancer, but our chances of developing the illness are just the same as anybody else’s who does not have a genetic mutation.

I cannot finish this article without a note of encouragement to all my readers: if you have the slightest suspicion that there may be a genetic disease in your family, please speak to your GP. Remember: early detection saves lives!

If you wish to learn more about the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, please visit the following links:

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet

http://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/testing/genetic/pos_results

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/91/15/1310/2543764/Cancer-Risks-in-BRCA2-Mutation-Carriers