About this One Place Study

Since I discovered my grandfather’s identity, background and family origins in the early 2000s (click here to read more), I have been fascinated by my family’s historical and genealogical ties to Italy. My dad’s biological father was born in New York City in 1916 to Italian immigrant parents originally from the region of Piedmont. My great-grandfather Giacomo Ameglio came from the small hamlet of Casalotto, in the municipality of Mombaruzzo (then in the province of Alessandria, now in the province of Asti), while my great-grandmother Giovanna Amerio was from the nearby village of San Marzano Oliveto (also in Asti).

My great-grandmother, one of twelve siblings including three sets of twins, belonged to a large family which had lived in San Marzano Oliveto for at least three hundred years. Unfortunately, the poverty faced by my family led to the untimely death of some of my great-grandmother’s relatives, including several of her brothers and sisters. To escape a bleak and uncertain future, she emigrated to America at the beginning of the twentieth century, following in the footsteps of her older brother Giacomo and sister Cesarina. In America, Giovanna married and had her only son – my grandfather – but never returned to Italy, as she died at the young age of 24. My great-grandfather sent his son to be raised by his paternal grandmother, and ultimately remarried. These events undoubtedly led to the eventual severing of relations between my family and that of my great-grandmother’s relatives in San Marzano Oliveto.

It is obvious that many of my great-grandmother’s relatives lived on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond. Several ended up settling in places with large Italian communities, like the United States and Argentina, while many of her more distant relations emigrated, as I later discovered, to England and even Australia. But whilst emigration played a considerable role in my family’s history, I should not forget that the immense majority of my distant cousins remained behind in Italy, though not necessarily in San Marzano Oliveto.

Noting the huge number of branches my Italian family tree has, and how often some surnames turn up time and time again, I decided to create this One Place Study not just to learn about my own family’s connection to the village, but the story of all those other families who at some time or other lived in San Marzano Oliveto. Many of them of course have a direct blood link to my family, while others remain disconnected from my family tree – though given the continuous repetition of some surnames, and the relatively small size of the village, I can only conclude that most sanmarzanese families indeed share a common ancestor somewhere along the line.

If you have a family connection to this picturesque Italian village, then please leave a comment below or send me an e-mail (click here to find out how) and I will be happy to cross-check the list of individuals that I have compiled over the years. You might also be interested in the following record collections:

- FamilySearch contains freely-accessible images for all births, marriages and deaths recorded during the period 1866-1910 by the civil registry office (Stato Civile) in San Marzano Oliveto. Please note that the births for the year 1901 appear to be missing from the collection.

- The Italian portal Antenati features deaths and marriages registered in san Marzano Oliveto between 1911 and 1926. Please note that the registers for the years 1914, 1916, 1917 and 1918 appear to be missing from the collection.

- Antenati and Geneanet both feature births, marriages and deaths recorded under the so-called Napoleonic Civil Registry, when the area came under French influence. The collection covers the period 1804-1813.

- For those of you whose ancestors emigrated to another country, you will also find useful records (e.g. passenger lists, census returns, naturalisation records, etc.) on websites such as Ancestry and FindMyPast. A subscription may be required to access these collections.

The following is a list of surnames that can be found in my family tree. Naturally, as my research continues, further surnames will be added to the list. To this I should add an extremely long list of surnames, some with a direct connection to my family, which either have or have had a presence in San Marzano Oliveto.

- Amerio

- Asinari (possibly related to the Asinari di San Marzano family who were ennobled and elevated to the rank of marquis)

- Barbero

- Bocchino

- Boggero (originally from Rocchetta Palafea)

- Bosca (originally from Canelli)

- Bussi (originally from Calosso)

- Giovine

- Parodi (originally from Costigliole d’Asti)

- Piemonte

- Poggio

- Saracci

- Sardi (two branches, one originally from Canelli and one from Costigliole d’Asti)

- Scagliola (originally from Calosso)

- Terzano

- Viazzi (originally from Rocchetta Palafea)

This “one place study” has been registered as such with the Society of One Place Studies and can also be found on the Registry of One Place Studies.

History

The village that would later come to be known as San Marzano Oliveto began to grow on a hilltop location on the edge of an old Roman road about two thousand years ago. As time wore on, additional buildings (defensive walls, a castle…) began to be erected around the area. Unlike today, the surrounding territory was dominated not by vineyards and orchards, but by dense forests and wilderness, as well as the olive groves that lent the village its suffix: Oliveto.

Although known originally as San Marziano in honour of the early Christian bishop of Tortona, San Marzano’s suffix was officially incorporated as part of the town’s name in 1862. Legend has it that this is due to the abundance of olive trees that had once populated the area. Today, olive trees scarcely grow in the area, and have been replaced by orchards where apples and pears are grown, as well as vineyards. Truffles have also become part of the area’s staple produce. One possible alternative that could explain the village’s unusual suffix, as given by Egidio Colla in his excellent history of the town, is that in the local dialect the letters r and l tend to be used interchangeably. In fact the nearby Mount Oliveto is known locally as “O rivè”, which translates roughly as a sloping terrain. This hypothesis seems to make much more sense if one notices the orography of the area. Whatever the origin of the town’s suffix, the veneration of Saint Martian, the village’s patron saint, obviously dates to a much earlier period.

Often caught between opposing neighbouring landlords, the village became part of a borderland march with a decisively defensive purpose in the middle ages. In 1382 count Amadeus of Savoy, lord of Asti, gave the feudal possession of San Marzano to Francesco Asinari, while other surrounding locations were given to Francesco’s brothers. The next two centuries saw San Marzano change hands many times. In 1531 the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V conferred the city of Asti and nearby territories (including San Marzano) to Charles III, Duke of Savoy. The Asinari family, meanwhile, retained the local lordship of the town and spread its branches into various local dynasties.

The 18th century was a time of drastic changes for Piedmont. Bad harvests and epidemics took a severe toll on the population, particularly in the 1730s and again in the 1790s. Despite the relative proximity of the Piedmontese-French border, the effects of the French Revolution were not immediately felt in San Marzano. It was not until Bonaparte’s army entered Piedmont in 1798, and the subsequent incorporation of the area into the French Empire, that life began to change for the local population dramatically. Meanwhile, Filippo Antonio Asinari (1767-1828), by then Maquis of San Marzano, became a trusted man in Napoleon’s First Empire, and was duly sent as ambassador to Berlin. By 1814, however, as Napoleon’s forces retreated, the Savoy dynasty had regained its footing in Piedmont.

The 19th century brought about in Italy the Risorgimento, and with it, a political movement to unify under the same flag all Italian-speaking countries and fend off all foreign influence, particularly in the Austrian satellite states (Modena, Tuscany…) as well as in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in the south, ruled by an offshoot branch of the Spanish Bourbons.

Italian unification did not come about in a single moment, nor would it have been necessarily something which continuously occupied my ancestors’ minds. They would have been much more concerned with gathering seasonal crops, wondering what the effects that the adverse weather might be on their livelihoods, being conscripted into the army, or whether taxes would be increased. Most inhabitants of San Marzano were poor agricultural labourers and worked the land that surrounded their unpretentious dwellings. Many may have been seasonal workers who travelled to Turin to work in the silk industry. Epidemics were also a constant fear, and as the 20th century drew closer, for the majority of them emigration became the only hope of escape from their meagre existence. Many chose the larger centres of Canelli or Nizza Monferrato as their destination; but the most adventurous made it to Turin, the regional capital, or Genoa, which in time granted them plenty of opportunities to emigrate overseas, be it to the United States, Argentina or even farther.

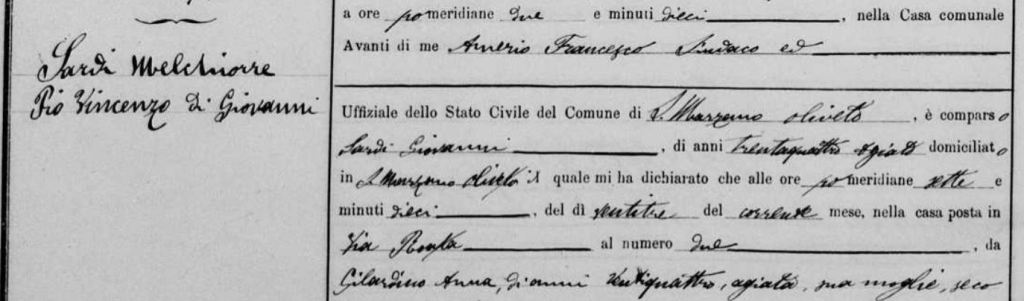

One of the town’s main claims to fame today comes from the fact that it is the birthplace of Vincent Sardi (born Melchiore Pio Vincenzo Sardi). Born in 1885 to Giovanni Sardi and Anna Gilardino, Vincent later emigrated to New York City and opened his first eatery, The Little Restaurant, in 1921. His success allowed him to open another restaurant in 1927, the now world-famous Sardi’s. Incidentally, I believe Vincent’s mother Anna Gilardino may be a distant cousin of my great-grandmother’s – just saying, in case I am ever in New York City and can claim a free meal at Sardi’s!).

World War I

After Italy entered World War I in May 1915, many Italian men were conscripted into the army. Most of the military action took place in the north-east of Italy and in present-day Slovenia, where the Italian army struggled to take over territories occupied or administered at the time by the Austro-Hungarian empire.

Like most Italian villages, San Marzano Oliveto had its share of personal losses during the conflict. The war memorial, located on the edge of the village centre, is a permanent reminder to their memory. Click here to read my research into every individual soldier who gave his life for his country in WWI.

In 1929, during the Fascist period, the municipality of San Marzano Oliveto was merged with neighbouring Moasca, being known until 1947 as San Marzano-Moasca. The consequences of World War II would also be felt close as home, and several men from San Marzano Oliveto are today remembered on the war memorial.

San Marzano Oliveto is today a placid village perched on a hilltop overlooking the Monferrato region. Its main claim to fame is perhaps the food and wine grown locally, as the impressive views it offers from the centre of the village. But to me, San Marzano Oliveto represents much more: the starting point of my great-grandmother’s journey to a new life in America. While her life may have been cut short at just 24 years of age, I hope I will be able to tell her story – and that of her many relatives – for many years to come through this One Place Study.