These last two months I have been kept very busy by delving deeper and deeper into my Italian ancestry. Ever since I discovered that at least two of my great-great-great-grandparents shared the same surname (Terzano), I wondered whether these two distinct lineages were actually related to each other, considering they came from the same tiny village: San Marzano Oliveto (Asti, Piedmont).

While I have yet to uncover the most recent common ancestor of those two lines (if indeed they are related, of course), I have rather excitingly discovered that I have two further surnames which are also repeated more than once on my family tree: Barbero and Amerio. It is the latter one I want to talk to you about today.

Amerio was my great-grandmother’s maiden name, and obviously the surname came down to her via her father’s paternal line, going as far back as the mid-18th century, to a Carlo Giuseppe Amerio. But my great-grandmother’s maternal grandmother was herself the daughter of Rosa Maria Amerio (1811-1874), the eldest of ten children and herself the mother of at least eleven others, at least three of whom she would survive. My most recent discoveries, thanks in part to a local researcher with access to records that are not available online, have enabled me to expand her paternal family tree even further.

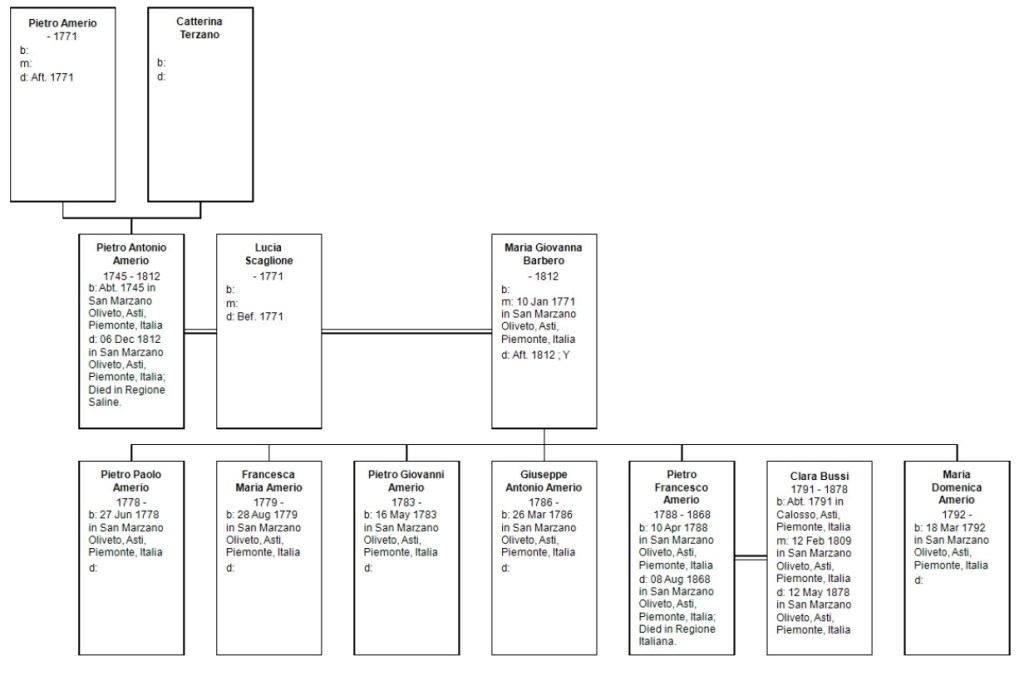

Rosa Maria’s father, Pietro Francesco Amerio (1788-1868) was, as I already knew, the son of a Pietro Antonio Amerio (c.1745-1812) – son of Pietro Amerio – and of his second wife Maria Giovanna Barbero – herself the daughter of Pietro Francesco Barbero, after whom Rosa Maria’s father was presumably named. For some time I have known that Pietro Antonio and Maria Giovanna were married in 1771, and that he had been married at least once before (when, and for how long, I do not know); whether there were any children born to that earlier marriage remains a mystery for now. However, considering that my ancestor’s union to Maria Giovanna took place in 1771, and that the couple’s son was born in 1788, chances are there must have been quite a few children born to Pietro Antonio’s second marriage to Maria Giovanna Barbero.

Thanks to the local researcher, I was able to learn that the pair did indeed have at least one daughter in 1792, as well as four additional children (born in 1778, 1779, 1783 and 1786), as shown in the family tree below. Why there is a gap between 1771 and 1778 I cannot account for, but we’ll leave that aside for now.

At this stage, you should be aware that Italian genealogical research (in Piedmont at least) becomes a little bit trickier by the time you’re back into the 18th century: women’s maiden names are often replaced by married names on church records, which are kept in very spidery Latin rather than clear hand-written Italian. Being able to read the priest’s handwriting, and then managing to understand the Latin expressions, is in itself an extra difficulty. But these challenges are not always insurmountable, provided you learn how to lean on other crucial details provided in baptism records, like the names of the godparents.

Let’s take the baptism of Pietro Francesco’s elder brother Pietro Paolo (yes, my ancestors were not very original when it came to naming their children – and brace yourselves because there are more Pietros coming up in this story!). The child was baptised in 1778, as we know, to Pietro Antonio Amerio, son of Pietro, and to his wife Maria (no explicit reference to her second or maiden names is given, nor to her father’s Christian name). However, his godparents, who would have held him at the font, are mentioned: Matteo Amerio, son of Pietro, and Giulia, wife of Pietro Francesco Barbero. The record does not explicitly tell us that the godparents were in any way related to the child, but the fact that the godfather’s father shared the same name as the child’s paternal grandfather, and that the godmother’s husband shared the same name as the child’s maternal grandfather, certainly seems indicative of a family tradition of having a godparent from either side of the family, one paternal and one maternal.

When the couple’s next child, Francesca Maria, was baptised the following year, her only godparent mentioned was Maria Domenica Barbero, daughter of Pietro Francesco Barbero – likely to have been the child’s maternal aunt. Incidentally, in this instance the mother’s maiden name is also omitted from the record.

In 1783 Pietro Antonio and Maria Giovanna (maiden name once again not mentioned) welcomed their third child, who was rather unimaginatively baptised Pietro Giovanni. His godparents were named on the register as Pietro, son of Matteo Amerio, and Vittoria, daughter of Giovanni Ivaldi. While the Ivaldis’ connection to my family escape me, Matteo Amerio is a name we have already come across before. Onwards and upwards.

Move on three more years, to 1786, and we find ourselves before an additional baptismal entry, for a Giuseppe Antonio. This boy’s godparents were Giuseppe, son of Matteo Amerio, and Antonia, daughter of Pietro Francesco Barbero. Another case of a godfather chosen among the boy’s paternal relatives, and a godmother from the mother’s side? Oh, and let’s not forget the youngest of the family, Maria Domenica, whose baptism in 1792 was witnessed by her godparents, Lorenzo Olivero and Maria Amerio, daughter of Matteo Amerio. Helpfully, this time her mother’s maiden name is made explicit by mentioning that Maria Giovanna was the daughter of Pietro Francesco Barbero.

On the face of it, it seems increasingly likely that the maternal grandparents of these little Amerios were Pietro Francesco Barbero and possibly of a woman called Giulia (who may have been Maria Giovanna’s mother – or stepmother!). Maria Giovanna also seems to have had at least two sisters called Antonia and Maria Domenica, who were godmothers to her children born in 1779 and 1786.

Through my own research some time ago, I have already identified some family members of Matteo Amerio (his full name was, unsurprisingly, Pietro Matteo Amerio). I knew that he married in 1763, so he was probably about the same age as Pietro Antonio (remember that the latter had been married once prior to 1771). As they were both fathered by a man called Pietro Amerio, in view of their repeated godparenting tradition I think it highly likely that they were brothers – a theory reinforced by the fact that Pietro Antonio’s mother was called Catterina Terzano, the same name given to one of Pietro Matteo’s daughters (see family tree below).

In all, Pietro Matteo had at least seven children: Pietro, Antonia Benedetta, Rosa Veronica, Giovanni Battista, Francesco, Giuseppe and Maria Catterina. Two of them (Pietro and Giuseppe) are known to have stood as godparents to two of Pietro Antonio’s children, and Matteo was himself godfather to a third. Interestingly, though perhaps not all that coincidentally, in 1869 Antonia Benedetta passed away when she was in her eighties in an area of the village called Saline, the same area where her presumed uncle Pietro Antonio died in 1812.

All this is certainly pointing in the right direction, but as we all painfully know, a theory is just that: a theory. I now need to think “strategically” to prove or disprove it. The following records should be able to help me in this regard:

- Pietro Antonio’s baptism would confirm not just his father’s name (Pietro Amerio), but also his mother’s (Catterina Terzano?), which is noted in his death record in 1812. If I can retrieve the baptism of Pietro Matteo, who was also presumably born sometime around the 1740s (considering his 1763 marriage), I might be able to connect them definitively.

- Even if the respective mothers’ names are not the same, we cannot discard the possibility that Pietro Matteo and Pietro Antonio were paternal half-brothers (sons of the same father but not the same mother), in which case their father’s two marriages would need to be accounted for.

- I would also be keen to find out more about Pietro Antonio’s first marriage (prior to 1771), and find out if that union produced any issue, and whether those baptisms reinforce the godparenting tradition kept up in the 1770s and 1780s.

- If instinct is anything to go on, I am sure that the godfather of at least one of Pietro Matteo’s numerous children was Pietro Antonio himself. I would therefore love to find the baptisms of Pietro Matteo’s children and see if Pietro Antonio is mentioned on any.

All in all, this latest research has shown me that underneath spiritual connections between different family units, like that between a godparent and his or her godchild, there may be an actual family relationship lurking about. Let’s not forget that remarriages were so common at a time when women often died in childbirth that we need to keep an open mind about individuals being connected through a full (or half) relationship. But above all, this research has reminded me of the importance of keeping track of other families with identical surnames: little could I have known years ago when tracing Pietro Matteo’s family that one day I may have to contemplate having to add his many descendants to my family tree as closer cousins that I could have imagined. Stay tuned!